Who pays a tariff? And what if it’s you?

Leigh Caldwell

Leigh Caldwell

Donald Trump insists that his big, beautiful tariffs will be paid by the foreign countries who are ripping off the American consumer. The tariffs are a penalty for their past bad behaviour, and as such they will have to swallow the cost if they want to sell to Americans. Economists, on the other hand, think it’s the American people who will end up paying most of the cost. Who’s right?

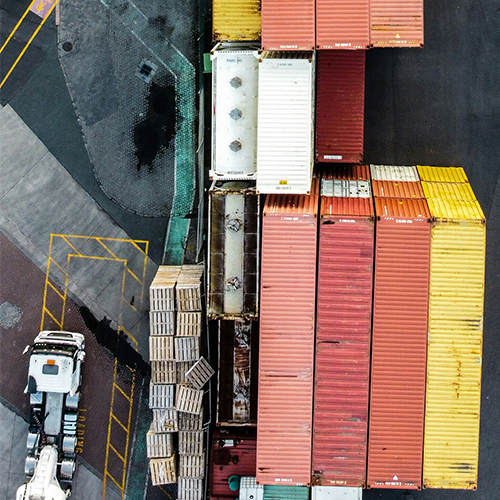

To answer this we have to look in more detail at how goods get into the country. There are more than just two parties involved. Ultimately, the tariff could be paid by any of several parties – foreign suppliers, domestic distributors, retailers or consumers. And if you’re in that value chain, how can you make sure the burden doesn’t land on you?

Albertson’s, the American grocery chain, sent a letter to its suppliers this week insisting they would not pay higher prices to cover any tariff costs. Which presents a big difficulty for someone who has agreed to charge a fixed price of 50c per banana, but is now paying an extra 10c in tax.

Their suppliers now have three choices: absorb the tariffs themselves, stop supplying Albertson’s, or try to negotiate a price increase regardless of the letter. For many suppliers, the tariffs might be greater than their profit margins and they will be unable to absorb the cost. Perhaps they can put some pressure on their own suppliers overseas to reduce prices, but in most cases those producers will still be able to sell to non-US customers for roughly what they’re charging now, so they will have little incentive to cut their own prices. A reduction in demand could lead to lower prices overall, so producers may end up absorbing some of the cost.

The answer depends on a series of elasticity numbers. Consumer demand elasticity determines how much less of something a consumer buys when the price goes up. Producer supply elasticity tells us how much less of the commodity will be produced when the price goes down. The final price is determined by the point where demand and supply curves cross – which in turn depends on those elasticities. Cross-elasticities tell us how much people will substitute one product for another when the price goes up or down; for example if the price of Canadian bacon goes up, how many people will buy American ham instead? (Which in turn will push up the price of American ham, as there isn’t an unlimited supply! So it’s hard to completely escape some kind of price pressure.)

Company profit margins aren’t fixed either – they are a function of the level of competition, the substitutability of their products, and customer loyalty and other barriers to brand switching. The less competition, the less substitution, and the higher the barriers, the stronger a position the company is in to maintain margins.

In most cases, this all ends up with consumers paying most of the cost of a tariff, with the foreign producers absorbing a minority of the impact. Intermediaries such as distributors and retailers will take a short-term hit but shake out to roughly the same margins as they had before. But the details and amounts will vary across categories and even across companies.

The US economy is surprisingly light on imports (15% of GDP) and exports (11%). These numbers rank it 192nd in the world, out of 205 countries. So the impact will be less than it would be in many other territories. But this 15% is weighted towards very noticeable segments of the market such as groceries, clothes, electronics, cars and other physical goods. Pricing here is often more concrete and visible than in sectors like services, media and digital products whose prices won’t be affected much by this policy. This means that companies’ decisions on pricing will be very visible, and with a lot of media focus, it will be hard to raise prices without being noticed.

Albertson’s has taken an aggressive stance to pre-empt supplier cost increases and put it in a stronger negotiating position, but when suppliers run up against the hard edges of what they can and cannot afford, it will stop working.

Other brands and retailers will be considering different approaches:

- Raise prices and explain the reasoning to consumers

- Shift product mix towards domestic products and away from imported ones, where possible

- Use pricing mechanics to dilute the emotional impact of price increases

- Take the opportunity to reshuffle prices and unstick old margin decisions that you’ve been stuck with

Different consumers in each sector will respond differently to these tactics. So I recommend researching a mix of approaches – set up a simulated shopping shelf and trial a range of pricing tactics to see which have the biggest impact on volume and brand appeal. This is not an entirely unique situation, how you can approach this problem and the possible subsequent solutions require similar methods that might have been used during the cost-of-living crisis of 2023. Two years ago our own research found a distinctive set of tactics that were most readily accepted by consumers, with the greatest success at increasing margin and preserving volume. Have a look at what we discovered back then: