How to solve a problem like claimed vs actual?

Leigh Caldwell

Leigh Caldwell

A man sits in the boardroom of a global packaged food company. “We need to encourage recycling” he says. “Sustainability is part of our value proposition, it’s in our brand values” he continues. “Is the messaging on our packaging encouraging our customers to think about the environment? Is it encouraging people to recycle?”

Our boardroom hero is unwittingly part of an archetype story. He’s our main character and he has a challenge. He sends his trusty fellowship of market researchers out to ascertain the truth of their sustainable packaging activities. Act One is underway.

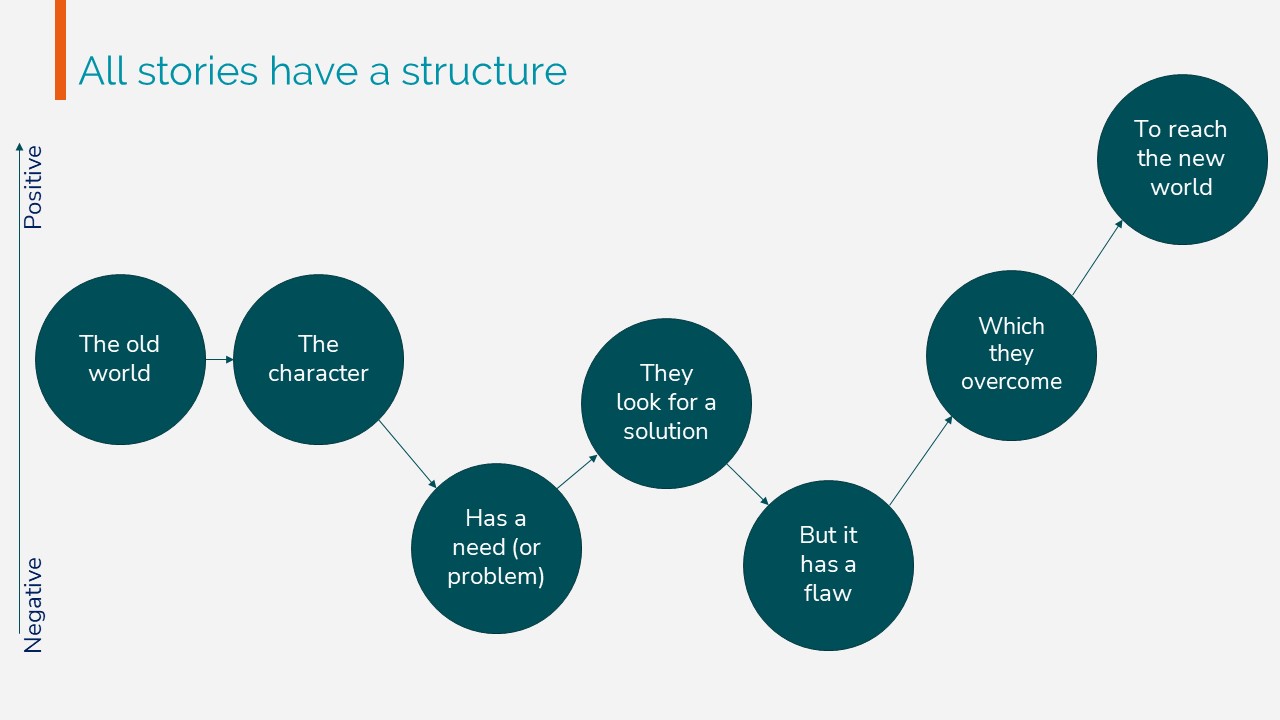

Every classic story from movies or literature has three acts. Act One introduces the characters and their problem, then in Act Two they seek out a solution and uncover even more challenges. In Act Three everything comes together and their goal is achieved.

Our heroes are wrestling with their market research challenge. And in true act two form, the plucky fellowship believe they have overcome the monster. But they approached it the same way they always do, and asked a standard question:

“How much of your household waste do you recycle”

- 0% to 20%

- 21% to 40%

- 41% to 60%

- 61% to 80%

- 81% to 100%

The majority of customers choose between 61% and 80%. The fellowship returns to the boardroom with news of their victory. “But wait a sec”, the qualitative team interrupts, “that doesn’t quite follow the ethnography we’ve been doing”. The number is probably more like 40%. And just like that the solution is flawed, and the monster resurrected for the big act three set piece battle. But in order to vanquish it, the fellowship needs a new strategy, a new approach.

It’s easy to see why we engage with narrative and story. Our brains are hardwired to react and engage with stories, and use them as ways of communicating information. It’s something we have been doing since the dawn of humanity. It’s also a way in which our brain processes information, and imagines future scenarios. The story archetype above is also how we process the imagined scenarios that result in things like purchasing decisions, we call it System 3.

Standard research questions give us answers based on previous experience or in desired intent. System 3, which asks consumers to tell us stories rather than click a tick box, dispenses with standard questioning to uncover the hidden behaviours and motivations that can only be accessed in the narrative mind. These techniques also help you find the “why” behind the “what”.

If our fellowship had used System 3 techniques the first time round, they would have found that people certainly overstate the amount they recycle. They would have discovered how emotions like guilt play a role in this overestimation, but also how those emotions are sometimes displaced onto retailers and brands rather than the consumer themselves. They would have discovered that there are also a number of key associations with recycling linked in the mind of the consumers - “values”, “community” and “support”. While the traditional research would have only given surface, and sometimes incorrect, views on personal behaviours. System 3 allows you a better understanding of actual behaviour, stripped of biases, allowing you a better understanding of the status quo. But it also allows you a view of the “why” behind the “what”. The action of placing an empty container in the recycling bin is not an act devoid of emotion or of meaning to the consumer. By understanding that “why” you can better understand and change behaviours.

Understanding this gives you the “where next”. Using behavioural science our hero in the boardroom would have known that the “This packaging is 100% recyclable” was encouraging nothing. He would have known that changing the message to something like “We value quality of life for our communities, caring about life on Earth, and inclusive support for fair trade for everyone. We encourage you to recycle this carton.” Appeals to key emotional hooks, links to associations with shared values, and at the same time anchoring the concept of the recycling of the packaging in a notion of community.

Our fellowship could have skipped straight to the third act and defeated the monster the first time round using behavioural science. It would make a less compelling film, but a more compelling business solution, saving money, time, and getting a deeper understanding of the customer.